Broadway Musical Time Machine: Looking Back at Into the Woods

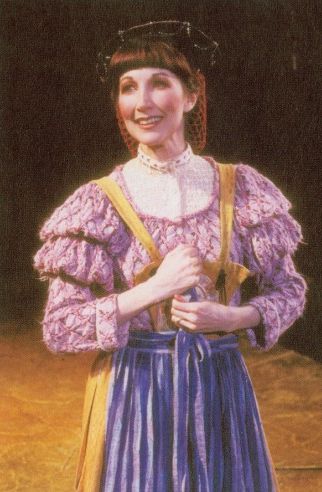

Joanna Gleason

Coming off their Pulitzer Prize-winning artistic success of Sunday in the Park with George, composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim and book writer/director James Lapine would turn their eyes to the world of fairy tales for their next Broadway musical. This would not be the Disney world of fairy tales with altruistic magic and happy-ever-afters giving us warm fuzzies. No, this musical would delve into the deep and dark psychologies of fairy tales, exploring the grimmest of Grimm fairy tales, violence in tact, but moral ambiguity in question. The result would be the now-classic Into the Woods.

Into the Woods took fairy tales beyond their logical, happy-ever-after conclusions, and plunged into the consequence of the characters’ actions and the means by which they secured the fruition of their wishes. Instead of absolutes that traditional fairy tales dealt in (good is so good, bad is so bad), Into the Woods put some of our favorite storybook characters into a land of moral ambiguity. Good people could make bad choices. Nice people die. Witches could be right and giants could be good. It messed with our sense of childhood, taking us to dark places in or psyche where we had to challenge our perceptions and moral codes. Many critics cited the show’s ambiguities as a detraction, but many fans of the show (and there are many) point to them as key to the musical’s resonance. We’ve all been burnt by buying into happy endings.

Bernadette Peters, Chip Zien, Kim Crosby, Ben Wright and Danielle Ferland

Into the Woods, all psychological babble aside, is also a very entertaining musical with perhaps the most accessibility of all Sondheim musicals. Most people enjoy fairy tales, and though these interpretations hardly mirrored Disney, Into the Woods didn’t mind occasionally poking fun at the notions that Disney animated classic’s instilled. We all laughed when a prince turned out to not be as charming as he was assumed. Book writer Lapine navigated in and out of wit, wisdom, and irony, created an intricate quest story (at times farcical and at times deeply emotional) of a childless baker and his wife who are given a limited time frame to gather ingredients for a spell: “a cow as white as milk, a cape as red as blood, hair as yellow as corn, and slipper as pure as gold.” Of course, this brings Jack and the Beanstalk, Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel, and Cinderella together in one wood, each for their own moral epiphanies.

Obviously, the highlight of any Stephen Sondheim musical is the Stephen Sondheim score. Into the Woods did not fail to delight in this regard, with many numbers exploring the parent/child relationship as a recurring theme throughout. “Children Will Listen”, “Stay with Me”, “No One Is Alone”, and “No More” (a song I will never forgive being cut from the film version) all touched on how the actions we take and the words we use shape relationships and shape the future. Has there ever been a more haunting lyric that “Careful, no one is alone”? Has there ever been a more meaningful lyric than “Careful the spell you cast, not just on children. Sometimes the spell may last past what you can see and turn against you”? The score of Into the Woods moves far beyond mere psychology in demonstrating that complicated parent/child dynamic.

Chip Zien and Tom Aldredge

Some interesting facts about Into the Woods:

- Into the Woods opened at Broadway’s Martin Beck Theatre on November 5th, 1987, running for 765 performances.

- Into the Woods was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Musical, but lost to The Phantom of the Opera. It did, however, win for Best Book of a Musical, Best Score, and Best Leading Actress in a Musical (Joanna Gleason as The Baker’s Wife).

- During Into the Woods’s original Broadway run, a large giant’s foot hung over the side of the Martin Beck Theatre while another one was poised on the theatre’s roof to appear as if it would come smashing down on 45th Street.