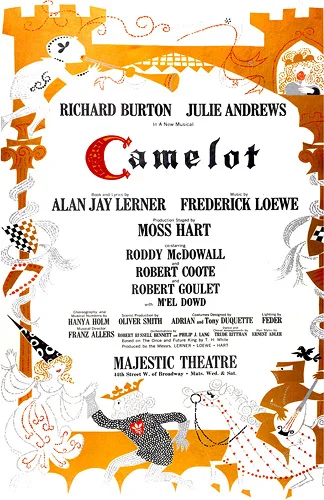

Broadway Musical Time Machine: Looking Back at Camelot

Lerner and Loewe are considered by many, after Rodgers and Hammerstein, to be the “duo supreme” of musical theatre composing teams. They certainly got onboard for the Rodgers and Hammerstein formula, and many of their musicals owe their success to that template. From their early scores for Brigadoon and Paint Your Wagon, to film with Gigi and The Little Prince, to their masterpiece My Fair Lady, the partnership yielded some of the most elegant, sophisticated, and memorable music in the history of musicals.

My Fair Lady represented the apex of their partnership. The 1956 musical was their crowning achievement, never to be topped and certainly never to be imitated. Interestingly, they tried to both top and imitate themselves for their next collaboration: Camelot. A success like My Fair Lady can set expectations high. Audiences want to love your next show as much as they did the last. Critics want your next show to build upon what you demonstrated with your previous show. The artist in you wants to capture lightening in a bottle again. No matter what followed My Fair Lady, Lerner and Loewe were going to spend some time (of their own and of others’ accords) playing the comparison game.

For their next venture, they chose The Once and Future King, a lengthy novel by T.H. White about the life and legend of King Arthur. It is a mammoth tome, and it soon became clear that it needed pairing down to tell an effective story. They chose roughly one-quarter of the piece, the story of Arthur’s marriage to Guenevere, her romance with Sir Lancelot, and the establishment of the utopic kingdom of Camelot and its subsequent fall. The musical drew from some of the best of My Fair Lady including Julie Andrews to play Guenevere, character actor Robert Coote to play Pellinore, Moss Hart to direct, Hanya Holm as choreographer, Franz Allers as conductor, and Oliver Smith to design the scenery. Most of the dream team had returned, but the magic of My Fair Lady was not to be repeated. The newly-christened Camelot was to see a series trials on a par with the Book of Job.

To begin with, pairing down The Once and Future King proved to be a daunting task; there was just too much content. In out-of-town tryouts, Camelot was running at a lengthy 4 ½ hours, which would mean the show would run too long for audiences to make their trains once the show reached its NYC destination. Never mind the fact that most theatregoers were used to shows that ran a more manageable 2 ½ hours. Director Moss Hart would have health problems throughout the production’s materialization and he would suffer a fatal heart attack not long after the show opened. The musical also put a certain amount of strain on composer Frederick Loewe who opted to leave writing for the musical theatre after the Camelot experience (He’d come back to write a few new songs for Gigi in 1973).

When Camelot did open, it was to generally positive, if not enthusiastic, reviews, though it was still a very lengthy musical by the standards of the day. Appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show would help generate enthusiasm for the show, bringing some of its more exciting numbers to the mass audience that television afforded. Camelot the musical has gained, in our collective minds, the reputation for being a bigger hit than it was, perhaps due to its eventual association with John F. Kennedy’s legacy. It did, however, manage a healthy run of 873 performances. At the Tony Awards, the musical was bested by Bye, Bye, Birdie in the Best Musical category, but Richard Burton won for Best Actor and Camelot also picked up a handful of design awards for its exquisitely opulent production.

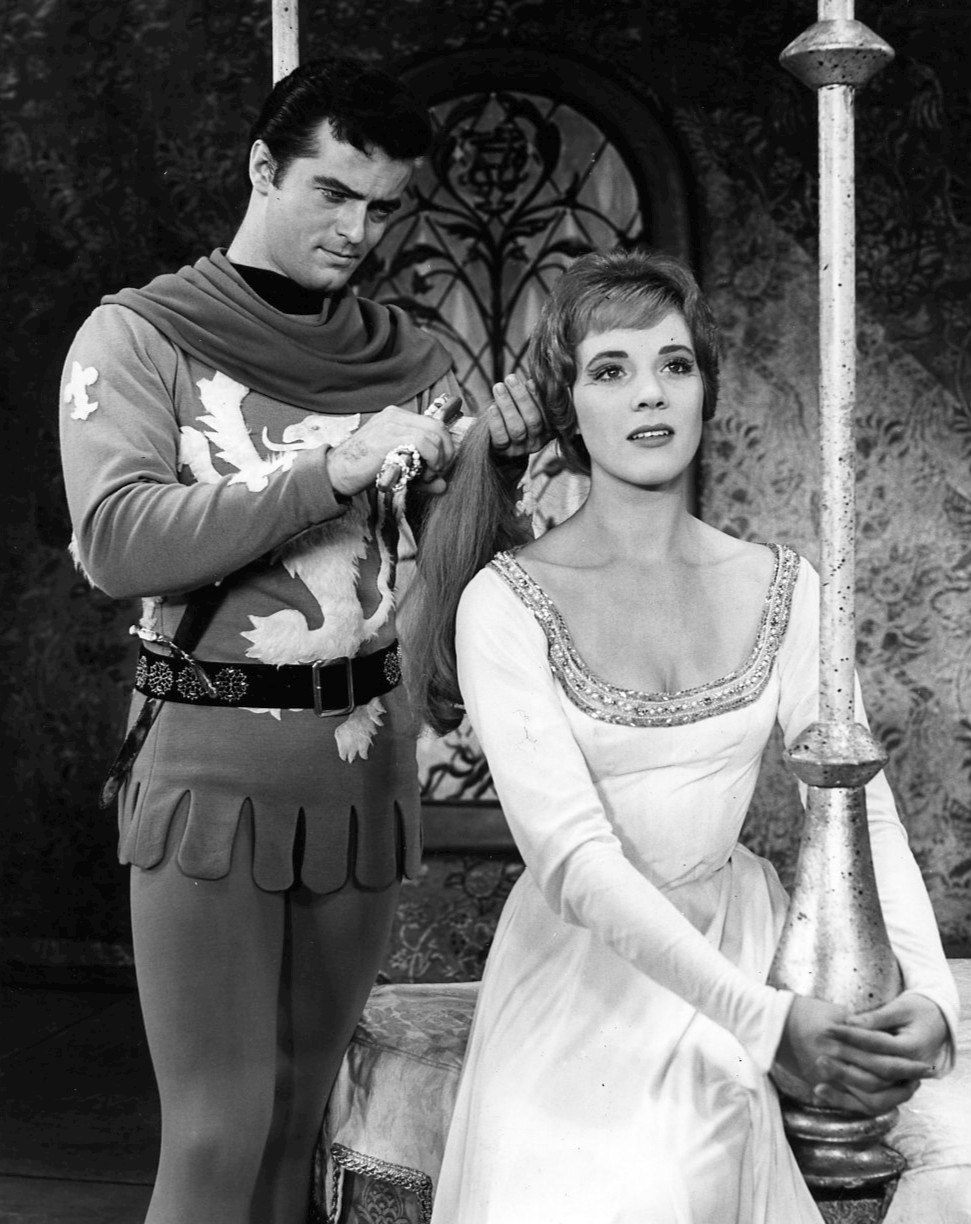

Christine Ebersole and Richard Burton in Camelot.

In the end, productions of Camelot are not as frequent as they used to be. Perhaps its brand of idealism is faded, the themes too hopeful for the jaded world of today. Maybe it’s just too long and producers understand that audiences are unlikely to sit for its entirety? It’s a shame, because the Lerner and Loewe score deserves to be heard and often. Maybe someday a director or producer will crack the code of how to make Camelot work for contemporary audiences without sacrificing its heart. An idealistic thought on a par with the imaginary kingdom itself.

Some interesting facts about Camelot:

- Camelot opened at Broadway’s Majestic Theatre on December 3, 1960 where it ran for 873 performances.

- The original cast album of Camelot was enormously successful, the best-selling LP in America for 60 weeks.

- Though nominated for a Tony Award, Julie Andrews lost to Elizabeth Seal for Irma La Douce. This would be her last nomination until 1996 when she was nominated for Victor/Victoria, an honor she would reject in a demonstration of solidarity with the show’s cast, crew and designers, many of which she felt many were “egregiously overlooked” as nominees.

- The film version of Camelot, starring Richard Harris and Vanessa Redgrave, was a critical bomb and is generally considered one of the more painful adaptations of a stage musical for the screen.

- In 1981, a Broadway revival of Camelot was recorded and aired on HBO. The production starred Richard Harris.